I’ve been working on a simple python package called timesheet, it’s a tool to help you track the hours you work in a simple spreadsheet. My previously role had a brilliant flexible working strategy that relied on tracking the hours you worked, when I decided to leave that role I wanted to take a bit of it with me so I created timesheet.

How it works

timesheet has a simple command line interface:

python3 -m timesheet --help

usage: timesheet [-h] [-f [timesheet_file_path]] [-r] [-s [hh:mm]] [-e [hh:mm]]

Welcome to timesheet, a tool to help you log the hours you work. You are using the command line interface for timesheet.

options:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

-f [timesheet_file_path], --file [timesheet_file_path]

Provide file for timesheet (note if not created this will create file). (default: outputs/timesheet.csv)

-r, --reset Reset the timesheet file provided with file (-f/--file) argument. (default: False)

-s [hh:mm], --start [hh:mm]

Add start time (hh:mm) to timesheet file provided with file (-f/--file) argument. (default: None)

-e [hh:mm], --end [hh:mm]

Add end time (hh:mm) to timesheet file provided with file (-f/--file) argument. (default: None)

So you would add a start time with:

python3 -m timesheet --file outputs/timesheet.csv --start

Which updates a timesheet with a simple Comma Separated Values (CSV) structure:

| date | start_time | end_time | time_worked | notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023-03-13 | 08:24 | 12:00 | 03:36 | nothing of note |

| 2023-03-13 | 12:24 | 16:24 | 04:00 | |

| 2023-03-14 | 08:35 | 12:05 | 03:30 | nothing of note |

| 2023-03-14 | 12:45 | 16:55 | 04:10 | nothing of note |

| 2023-03-15 | 08:22 | 11:51 | 03:29 | nothing of note |

| 2023-03-15 | 12:15 | 17:05 | 04:50 | nothing of note |

| 2023-03-16 | 08:36 | 12:06 | 03:30 | a simple note |

| 2023-03-16 | 12:56 | 17:03 | 04:07 | nothing of note |

| 2023-07-09 | 15:18 | 00:00 |

What I’ve learnt

The main aim of developing timesheet was to condense some of my learning so far into a simple example project as well as expand my practical experience of building python packages. timesheet has the following key elements I want to highlight:

- Simple reuseable project structure

- Modular object oriented programming

- Unit testing with a high coverage

- Good documentation

I wanted to use this blog post to talk about my experience building timesheet and reflect on each of the above key elements.

Reusable project structure

To get me started, I wanted the simplest possible python package structure that I could understand and work within. There are plenty of useful resources on this (for example here and here) and I landed on:

📦my_package

┣ 📂data

┃ ┗ Put all your data in here

┣ 📂scripts

┃ ┗ Python scripts in here designed to called directly in command line

┣ 📂tests

┃ ┣ 📜__init__.py # required so python code registered within package

┃ ┗ Unit testing functions in here

┣ 📂my_package

┃ ┣ 📜__init__.py # required so python code registered within package

┃ ┣ 📜__main__.py # script called when you call package (python -m my_package)

┃ ┗ Package classes and modules in here

┣ 📜.gitignore # files to ignore (e.g. data folder)

┣ 📜.pre-commit-config.yaml # pre-commit workflow

┣ 📜LICENSE # open source licence

┣ 📜README.md # simple project documentation

┣ 📜requirements.txt # package requirements

┗ 📜setup.py # required for pip installation

The structure above will work nicely for all my python projects and hopefully encourage good practice without being overwhelming. Some cool things to note:

- You can install a reactive version of your package (with the above structure) by navigating to the package directory and running:

pip3 install -e .and the package will automatically update as you change the code

- Local imports of modules and classes within your package work really well using (this is setup via the

__init__.pyscripts in the structure above):from my_package import my_package_module_or_class

Modular object oriented programming

I spoke about the value of modularisation in my previous blog post on reproducibility. Here’s how I’ve put that into practice in timesheet:

timesheetis both modular with functions associated with different aspects oftimesheetbeing stored in separate scripts (each are then linked together and used via localimports). For example:timesheet/data_functions.py- functions for working with the clocking in/out datatimesheet/timesheet.py- a Timesheet class/object for storing and interacting with timesheet datatimesheet/command_line_interface_functions.py- functions fortimesheet’s command line interface

- All the functions defined throughout the

timesheetcodebase have docstrings, for example here’s one for a simple function to calculate time differences:def calculate_time_difference(start_time: datetime, end_time: datetime) -> timedelta: """Calculate difference between start and end time Args: start_time (datetime.time): start time end_time (datetime.time): end time Returns: datetime.time: difference between start and end time """ # Calculate time difference difference = end_time - start_time # Check time difference is positive if difference.total_seconds() < 0: raise Exception( f"The end_time provided ({end_time}) is not after the start_time ({start_time})" ) return difference - I’ve built a simple set of functions to test all of the

timesheetfunctions that is similarly modular and helps to make my codebase more robust as I continue to develop it

Unit testing with high coverage

Until building timesheet I hadn’t ever written any unit tests for my projects despite them being an integral part of developing reproducible and robust codebases. I’ve used developing the timesheet package as an opportunity to learn how to write unit tests and put that into practice.

The unit tests for timesheet are found in the timesheet/tests folder and target each of timesheet’s functions. These tests use the unittest python package.

Now the tests are written, testing timesheet is as simple as running this command:

python -m unittest

I’ve linked my test coverage to a badge in my README.md too:

To see how I’ve done this check out timesheet/scripts/update_test_coverage_badge.py - I’ll be writing a blog about this soon! ⏲

My key takeaway here is that unit tests, although intimidating, are easy to write (especially if you do them from the start) and are an incredibly useful tool as you are developing the codebase to ensure what you change isn’t having any unintended consequences.

Good documentation

I talked about my writing docstrings for my functions above, which are a really important part of timesheet’s documentation. I also wanted to use this opportunity to learn how to build project documentation using Sphinx.

For timesheet, I’ve set Sphinx up to create some simple documentation web pages by pulling all my code information from timesheet’s structure and docstrings (see the timesheet/docs folder to get an idea of how it’s setup). In the future, I’ll get the timesheet docs hosted on one of the many docs hosting services like readthedocs.

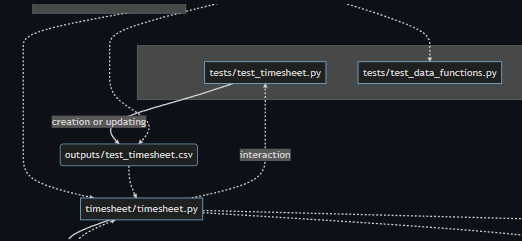

I also spent a fair bit of time on the timesheet/README.md (hopefully it shows) adding information on what timesheet is and how to use it. I added some cool features like an interactive workflow diagram created using mermaid (to show the structure of the codebase and how it interacts):

and a nice folder structure diagram that I built using Visual Studio Code’s file-tree-generator extension (like the one I have shown above).

Next steps

I’ve got some ideas for next steps for timesheet:

- As I noted above I want to host the documentation online using something like readthedocs

- I want to add functionality to show total hours worked per day and compare that to a target

- I’d like to build a graphical user interface for

timesheetfor people who don’t want to use the command line - I’d like to add an automatic logging feature that tracks locking and shutting down your computer and uses that to log hours work

Wrapping up

Anyways I’ve really enjoyed building timesheet and it’s going to be a brilliant resource for my future python projects. 🚀